David W.D. Dickson’s trailblazing career, spanning more than 40 years and five academic institutions, began at Michigan State University in the Department of English in 1948 when he became the university’s first Black faculty member and, a few years later, the first to be awarded MSU’s Distinguished Faculty Award. He also went on to become the first African American to lead a college or university in the state of New Jersey. However, the trajectory of his academic accomplishments first began in his childhood home.

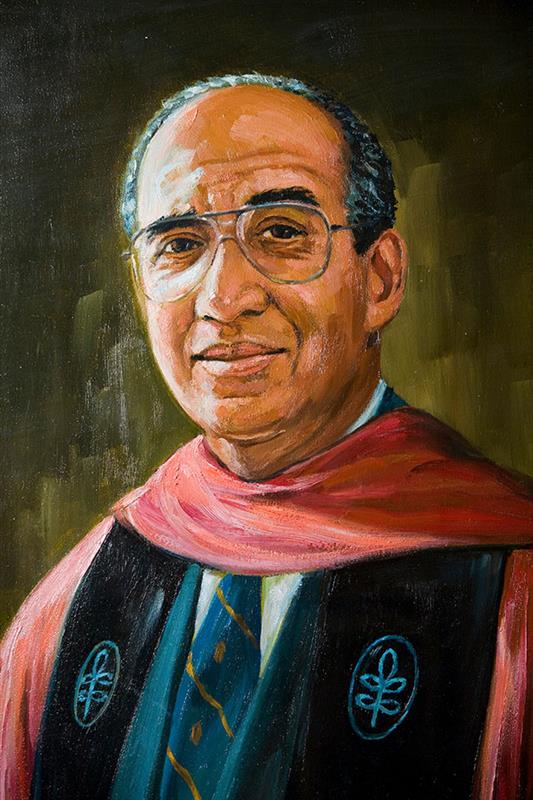

(Photo courtesy of MSU Archives & Historical Collections)

Born on February 16, 1919, in Portland, Maine, Dickson was the child of Jamaican immigrants who raised five academically exceptional children who each graduated at the top of their class at Portland High School. The four boys, who each received academic scholarships, all attended Bowdoin College and were the first four Black brothers to attend the college. But daughter Lois went to Radcliffe since Bowdoin didn’t accept women at the time.

David W.D. Dickson received straight As at Bowdoin, graduating summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa with a bachelor’s degree in English in 1941. He enrolled at Harvard in the fall of 1941 and received a Master of Arts degree in English Literature the following year. Drafted into the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1943 during World War II, he was tapped to attend Army Officer Candidate School, from which he graduated first in his class, and was assigned to be Adjutant to the Commanding Officer of the medical unit at Tuskegee Airfield in Alabama.

I was and have been throughout my life a cosmopolite. The blood of three continents flowed in my veins. I wanted to be a citizen of the world, a true internationalist, and to preach the gospel of interracial understanding and love to students.

Dr. David W.D. Dickson

After three years of service, he was discharged from the Army in 1946 and returned to his doctoral studies at Harvard. He later credited his time in the Army, working alongside men with far less education, with making him a better teacher, administrator, and person.

Dickson received his Ph.D. in English Literature from Harvard in 1949. His search for a faculty position wasn’t easy since he chose not to take the usual route of teaching at a Black college.

“I was and have been throughout my life a cosmopolite,” Dickson wrote in his 1995 book, Memoirs of an Isolate. “The blood of three continents flowed in my veins. I wanted to be a citizen of the world, a true internationalist, and to preach the gospel of interracial understanding and love to students.”

Breaking MSU’s Racial Barrier

At the time, opportunities were few for Black educators outside of Black colleges.

“There were perhaps only a half dozen white institutions nationally that would consider employing a Black man as a professor, and Harvard was not among them,” said Dickson’s son, David A. Dickson II, a retired Political Science Professor. “My dad was undaunted and applied to Michigan State.”

The Chair of MSU’s English Department at the time was Russel B. Nye, who David W.D. Dickson wrote was “very ready to dare to break the color bar of the university and the nouveau bourgeois town of East Lansing where no Blacks lived outside the dormitories.” Dickson became an Assistant Professor of English and was given the opportunity to live in an apartment on campus since there was no housing available for him in town. He was assigned to teach the “Bible as Literature” course that would not only become one of the English Department’s most popular but also confirm him as a devoted and enthusiastic educator.

There were perhaps only a half dozen white institutions nationally that would consider employing a Black man as a professor, and Harvard was not among them. My dad was undaunted and applied to Michigan State.

David A. Dickson II, son of David W.D. Dickson

“Very soon, my classes in Biblical Literature, required for majors in journalism, became very popular. Students no longer force-fed the Bible at home found the Old Testament especially a treasure trove of full-blooded biography, exciting narrative, and lyric and prophetic poetry of surpassing beauty and power,” Dickson wrote in his memoir. “My own enthusiasm for the work was contagious…My reputation as a teacher was readily recognized and I quickly gained promotion to Associate Professor.”

Dickson found that not only did his academic specialty, Biblical Literature, interest students, but all sorts of people as he gave many talks to many diversified groups. He also spent much time doing community service and helping advance the Black community. He even helped found the first Omega Psi Phi chapter in central Michigan.

“I spent too much of my time and talent in giving speeches in the community. As the only Black professor at a major college and university, I was soon on too many church and social agency boards,” he wrote. “On campus, I was asked to advise the only Black fraternity and expected to help solve any ‘color problems.’”

My own enthusiasm for the work was contagious…My reputation as a teacher was readily recognized and I quickly gained promotion to Associate Professor.

Dr. David W.D. Dickson

A full professorship did not come at MSU because he said he was “more concerned with teaching and community service than with developing a body of scholarship.”

“He did publish,” Dickson’s son said, “but his real passion was going into the classroom.”

For his teaching, he was awarded MSU’s inaugural Distinguished Faculty Award in 1952 (now called the William J. Beal Outstanding Faculty Award).

Finding a Home at the Height of Jim Crow

At the same time that his career was beginning, so too was his family, which also got its start at MSU. He met his first wife, Vera (Allen), while chaperoning a dance hosted by Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, the only Black fraternity on campus at the time. Married in 1951, the couple eventually had three children: son David and daughters Deborah and Deirdre.

But life in East Lansing at the height of Jim Crow segregation was not without its limitations. The couple attempted to buy a house, but continued to be met with opposition, redlining, and restrictive racial covenants.

(Photo courtesy of MSU Archives & Historical Collections)

“East Lansing was by no means ready for a Negro homeowner,” Dickson wrote in his memoir. “Even some of my liberal departmental colleagues urged me not to buy a home in their neighborhood and, therefore, depreciate their only considerable capital investment…When one bold salesman interested us in a pleasant house in nearby Okemos, the owner, a barber at the college, refused to sell and offend his neighbors.”

It wasn’t until MSU President John Hannah intervened that the Dicksons were able to purchase the home of the outgoing Dean of Women, a short distance from campus.

East Lansing was by no means ready for a Negro homeowner. Even some of my liberal departmental colleagues urged me not to buy a home in their neighborhood and, therefore, depreciate their only considerable capital investment.

Dr. David W.D. Dickson

Despite these obstacles, Dickson wrote that he enjoyed his time at MSU, both academically and socially, making friends and impressing colleagues across campus and within the Episcopal and Black Lansing communities.

“He was a deeply religious Episcopalian who considered joining the clergy,” Dickson’s son said about his dad. “Yet he was not sectarian, but a believer in pluralism and tolerance who learned Hebrew, among other languages, and respected people across religious, ethnic, and racial lines, focusing on their commonalities.”

In 1955, seven years after Dickson joined the faculty at MSU, the university hired a second Black professor, and in 1957, William Harrison Pipes became the first Black faculty member at MSU to be granted full professorship. In 1970, Clifton R. Wharton Jr. became president of MSU, making him the first Black president of a major U.S. university.

Breaking Barriers Beyond MSU

After 15 years at MSU, Dickson went on to academic and administrative appointments at Northern Michigan University, where he served as Chair of the Department of English, Dean of Arts and Sciences, and Vice President for Academic Affairs; Federal City College in Washington, D.C., where he was Vice President of Academic Affairs and Provost; SUNY Stony Brook, where he was Assistant to the President and Dean of Continuing and Developing Education; and on a chilly late-October afternoon in 1973, he was inaugurated as the fifth president of Montclair State University in New Jersey, becoming the first African American to lead a college or university in that state.

In his inaugural speech, the professor of 17th-century English literature, biblical literature, and the poetry of John Milton promised to seek at all times “abundant truth, concern for the wider college community, and an integration of body, mind, and spirit among members of the community.” The humanist core of his pledge that day had permeated his entire career. And during his decade-long tenure as President of Montclair State, he achieved that and much more.

According to Montclair State, Dickson’s tenure spurred “a period of rapid growth as the college completed the transition from teacher’s school to comprehensive institution.” Enrollment tripled to 14,000, the university added 30 undergraduate and graduate academic programs, and the campus gained 11 new buildings. Dickson also returned to the classroom once each year to teach Renaissance and Biblical Literature as Distinguished Professor of English. He retired as president in 1984 but continued to teach there until 1989. In 1995, Montclair State’s School of Humanities and Social Sciences building was named in his honor.

Dickson died on December 10, 2003, having lived a life unremarkable for the racist obstacles he encountered but remarkable for his refusal to yield to them — to yield his belief in the fundamental humanity, and commonality, of all people.

“He was proud of his West Indian roots — he never shied away from them — but he had a strong aversion to the most virulent forms of nationalism,” Dickson’s son said. “He always wanted to recognize the dignity of different groups, the commonalities among people that transcended ethnic, religious, and racial lines. And it was a very difficult thing to promote during his lifetime, and perhaps even more so now.”

(Written by Kimberly Popiolek with many thanks to Bowdoin College Library Special Collections & Archives for making David W.D. Dickson’s “Memoirs of an Isolate” available to help tell this story and to Aaron Tomak, Library Assistant at MSU Libraries, for his assistance.)